A user's guide to the New Zealand Avalanche Advisory

The New Zealand Avalanche Advisory (NZAA) provides an avalanche forecast for 13 regions of backcountry terrain in New Zealand. These forecasts are written by snow safety professionals based on the information they have about the current snow conditions and the expected weather for the forecast period.

The NZAA is an important source of information to help you plan your trip and make safe decisions in avalanche terrain. Avalanche education, your own observations in the field, and having the skills and equipment for companion rescue are also required for safe backcountry travel. It is your skills and decision-making that will keep you safe out there.

This page will provide a description and explanation of the different elements of an Avalanche Forecast. You can also skip to a particular area of the forecast by selecting below:

- Date and Time

- Key Message

- Danger Ratings

- Avalanche Problems

- Recent Avalanche Activity, Current Snowpack Conditions, Mountain Weather, and Sliding Danger

- Public Observations

- More Information

Date and Time

This is the date and time that the forecast was written and the period for which the forecast is valid.

When conditions are changing rapidly a forecast may be valid for a shorter time period and updated more regularly. When conditions are stable and little change is expected, forecasts may be valid for up to 72 hours. Always check the forecast as close as possible to the time when you plan to head out into the backcountry.

At the bottom of the forecast page you will see a box with a date in it, you can click on this to see historic forecasts. This is helpful when building a picture of how the snowpack has developed during the season.

Key Message

At the top of the page is a brief summary of the forecast. This provides important information about what to expect during the forecast period and things to keep in mind as you read the forecast. Think of this as the main point the forecaster wants you to take away from the forecast.

Danger Ratings

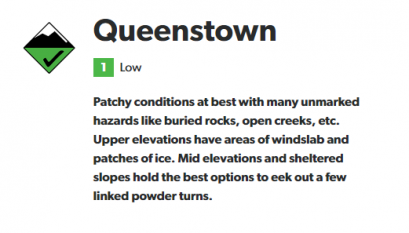

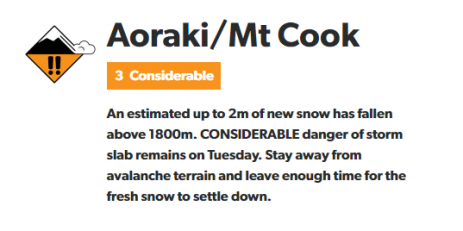

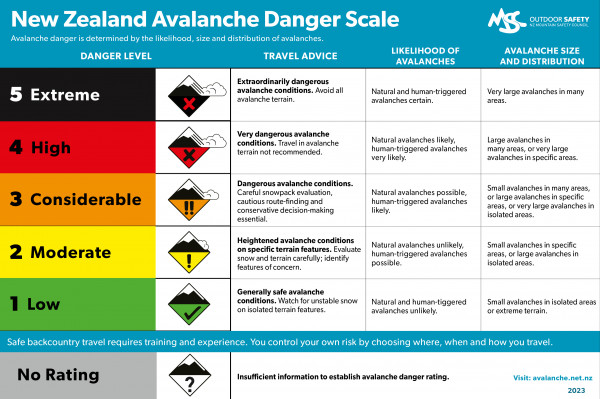

We use the New Zealand Avalanche Danger Scale, which is identical to the North American Avalanche Danger Scale and has been adopted by most English-speaking countries. The Danger Rating gives an overview of how hazardous the avalanche conditions are on a scale of Low, Moderate, Considerable, High or Extreme.

It is important to become familiar with the definitions of each Danger Rating (below). Especially important is the Travel Advice, as this should give you a clear idea of how to approach avalanche terrain with this rating. For example, the Moderate (yellow) rating tells you to ‘Evaluate snow and terrain carefully, identify features of concern’ whereas a Considerable (orange) rating advises you that ‘Careful snowpack evaluation, cautious route-finding and conservative decision-making are essential.’

The Danger Rating system is a broad tool covering a large area of terrain (the entire forecasting region). As a result, more information is needed to assist with your trip planning. Also, a variety of conditions can fall into each danger rating. For example, a Moderate rating means that there could be small avalanches in specific terrain or large avalanches in isolated (few) places. Reading further into the advisory will help you gather more detail on these specific conditions.

At the top of the advisory, an Overall Danger Rating is provided for the avalanche terrain in the forecast region. The overall danger rating is the highest Danger rating of all elevation bands.

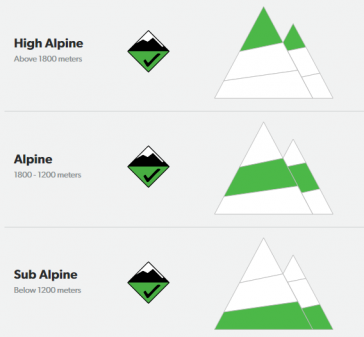

Below this, the region is broken down into three elevation bands which are each given a Danger Rating.

These are generally:

High Alpine - above 1800m

Alpine - 1800m – 1200m

Sub Alpine - Below 1200m

Exceptions:

- The Aoraki/Mt Cook region has higher elevation bands in the summer to take into account the significant amount of terrain above 1800m, and to better reflect the way this terrain is used in summer.

- The Wanaka region has slightly different elevations to allow for differentiation between areas in the region (Treble Cone backcountry vs. deep in Mt Aspiring National Park).

- The Tongariro region also has quite different elevation bands due to its elevation, terrain and usage compared to other regions.

Each of the elevation bands is also given its own Danger Rating.

Check the elevation bands for the specific regional forecast that you are using and use a TOPO map or other tools to understand what elevation bands you’ll travel through on your trip.

During Low danger, it may still be possible to trigger an avalanche.

A small avalanche can have major consequences when terrain traps are present. In general, the higher the danger rating, the fewer places there are where it is safe to travel. Avalanche danger will still exist at Low danger but will be far easier to avoid than at a Considerable danger level.

Avalanche Problems

Avalanches are categorised into nine different types. Each type or ‘problem’ has different characteristics and management strategies.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spring Conditions – this is not an avalanche type but a description of conditions that are usually firm or frozen in the morning and softening later in the day. Temperature and sun are the key variables that will affect avalanche conditions during Spring Conditions.

There may be up to three different Avalanche Problems in a forecast, these will generally be shown in priority order of concern. Sometimes the level of avalanche danger presented by two or more problems avalanche problems will be similar. This is reflected in the likelihood and size of expected avalanches.

The written description next to the Avalanche Problem is where you will find details such as how to manage the avalanche problem, terrain features where the problem may be found, weather conditions affecting the problem and specific travel advice. Further education and reading will give you the tools needed to use this information.

For each avalanche problem on the advisory you will also see the following descriptors:

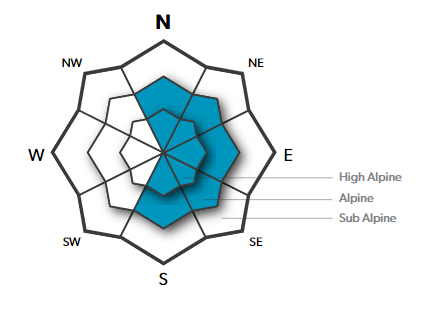

Aspect and Elevation Rose

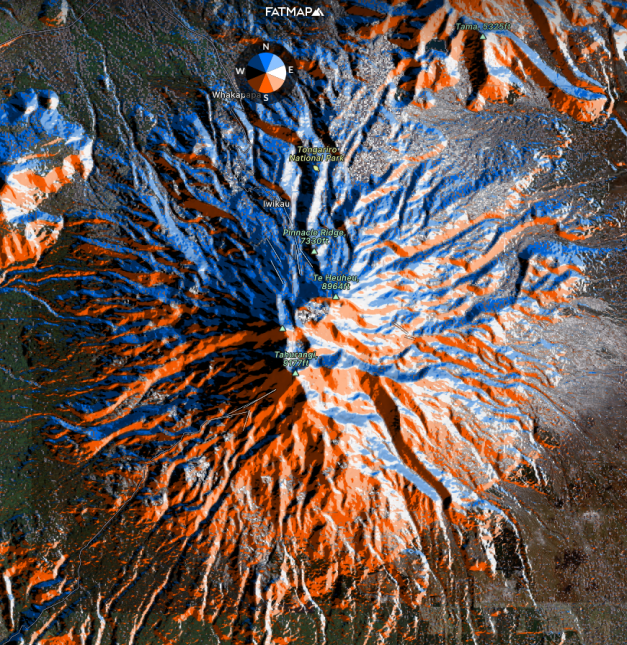

The Aspect and Elevation Rose shows you where you can expect to encounter the specific problem. Imagine the star-shaped diagram as the view looking directly down on a mountain. The inner section is the upper mountain or High Alpine, the middle section is the Alpine and the outer section is the Sub Alpine. Each aspect, or direction, is labelled with a compass direction.

This is a simplified representation of where the avalanche problem can be found. Because real mountains are not perfect diagrams it is important to consider the aspect (or compass direction) of specific terrain features along your planned route. Below is a map (from FatMap) with all of the different aspects shaded on Mt Ruapehu (the key is at the top). Even for such a round mountain, this shows how terrain features such as ridges, gullies, and rock outcrops can create features of different aspects on any side of the mountain.

Examples of how avalanche problems vary with aspect include; wind transporting snow from a certain direction and loading onto lee or sheltered slopes, cold or warm temperatures affecting the bonding of layers in the snowpack, or how the sun affects the snow depending on its arc in the sky at different times of the season.

Trend

Information about whether the avalanche problem is likely to become more dangerous, less dangerous or stay the same during the forecast period. This depends on the amount of time since snow has fallen, how the snowpack is changing over time, and the forecast weather.

For example, Wind Slab hazard may decrease over time if the wind eases and the bond of the slab to the old snow surface strengthens. The Wind Slab problem may increase within the forecast period if the wind is picking up during the day.

Time of day

Most avalanche problems will be a concern all day. However, some problems will only occur at certain times. The most common example of this is when Loose Wet avalanches are caused by the sun affecting new snow. In this case, a specific time of day may be given, such as between 1 pm-4 pm.

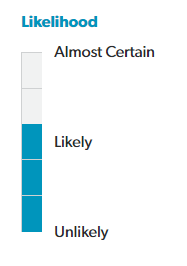

Likelihood

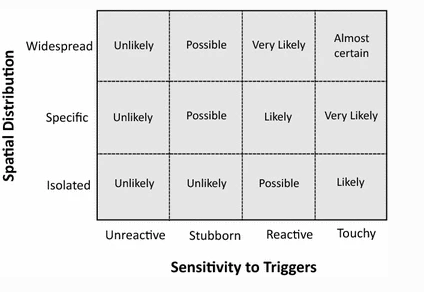

The likelihood scale shows how likely you are to trigger an avalanche of this type if you travel through terrain where this problem exists.

This information is important to consider in combination with the forecast avalanche size (below). If size and likelihood are both low, then the problem may be manageable in certain terrain. If the likelihood is low but you may trigger large avalanches, then these areas are best avoided.

The forecaster will combine information about how reactive or sensitive the problem is and the distribution of the problem in the terrain (is it found in few or many places) to assign a likelihood.

(Statham, G., Haegeli, P., Greene, E. et al. A conceptual model of avalanche hazard. Nat Hazards 90, 663–691 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-017-3070-5)

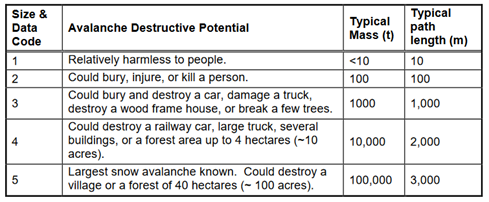

Size

This is the size of this avalanche type that may be triggered. Avalanche size is measured by the Destructive Scale (below) which ranges from size 1 to size 5. This scale takes into account the width, length and depth of a potential slide and also its potential to cause damage.

Small (size 1) avalanches may still be harmful when terrain traps such as cliffs, gullies or vegetation are present. Large avalanches are always dangerous and you may consider increasing your distance from the slope when choosing a lunch spot or campsite.

The Destructive Scale outlines the destructive potential, typical mass and typical path length of avalanches of a given 'size'.

(Page 51 in the NZ Guidelines and Recording Standards for Weather, Snowpack and Avalanche Observations)

Recent Avalanche Activity

A summary of recent avalanche activity in the region. This information comes from observations made by local operators, the forecasters themselves and Public Observations.

Current Snowpack Conditions

Specific information such as the depth of the snowpack, new snow and layers of concern. It may include the results of snowpack tests and a description of how the snowpack varies within the forecast region. This is generally a broad description of the snowpack in the region, but it may give a specific location where observations were made or snowpack tests were carried out.

Reading the advisory regularly and referring to previous forecasts will help you to form a more in-depth understanding of snowpack conditions.

Mountain Weather

A brief summary of the weather expected in the region for the forecast period and how this relates to avalanche conditions. You will also need to gather your own, more detailed, weather forecast when planning your trip.

Some of our favourite weather forecast sources are below, though you may have others you prefer. It's often best to look at a few sources to understand the range of possibilities.

Sliding Danger

Due to New Zealand’s maritime climate, we often experience icy conditions caused by the melting and re-freezing of surface snow and rain crusts. This section of the forecast provides a warning when these conditions occur and may include a recommendation to carry crampons and ice axe. As always, make sure you assess conditions carefully when you are in the mountains to anticipate hazards early and adjust your travel plans accordingly.

Public Observations

You can share your observations using the Public Observations page. Photos or information about avalanches, snow conditions or snow quality are all very useful and help the Avalanche Forecasters and other backcountry travellers in your region.

Keep Learning

Recognising avalanche terrain and minimising your exposure to danger while recreating there requires skills, knowledge and experience. The Avalanche Advisory is just one part of the equation.